Graduates of Minority-Serving Institutions Show High Law School Interest, But Have Fewer Admission Options

Our recent report, “Law School Applicants by Degrees: A Per Capita Analysis of the Top Feeder Schools,” expands on LSAC’s list of Top 240 Feeder Schools by analyzing “applicant concentration”—the number of law school applicants from an undergraduate feeder school compared to the number of bachelor’s degree recipients it produces. This percentage serves as a proxy for the level of interest in law school at each feeder institution.

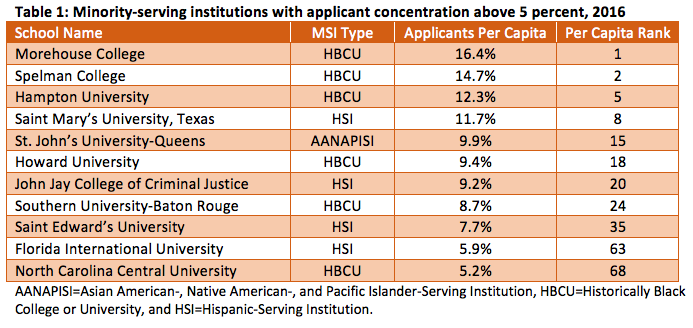

A key finding of the report is that several minority-serving institutions (MSI) produce a high concentration of applicants, despite generally having lower applicant volume. In fact, MSIs are disproportionately representative of schools with the highest applicant concentration: MSIs made up about 22 percent of the 233 schools in our analysis but represent 35 percent of the top 20 feeder schools by applicant concentration and 40 percent of the top 10. A total of 11 MSIs from the top feeder list had an applicant concentration greater than 5 percent, which exceeds the median of all top feeder schools (3.8 percent in 2016) (Table 1).

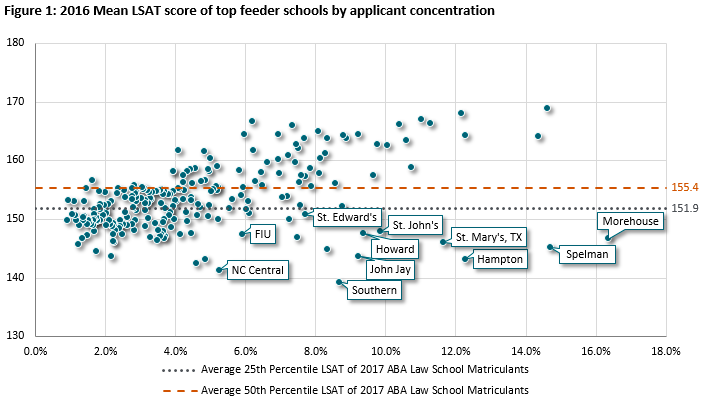

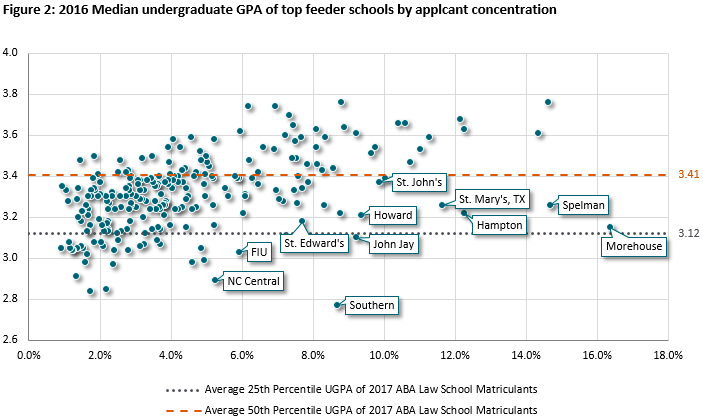

However, the admission profiles of applicants from these 11 schools tend to be less competitive compared to graduates of other feeder schools. Ranging from 139 to 151, their average LSAT scores fall below both the average 50th percentile LSAT score (155) and the average 25th percentile LSAT score (152) of ABA-approved law schools (Figure 1). Likewise, the median undergraduate GPA (UGPA) of applicants from these MSIs all fall below the average 50th percentile UGPA of matriculating law students (3.41) (Figure 2).

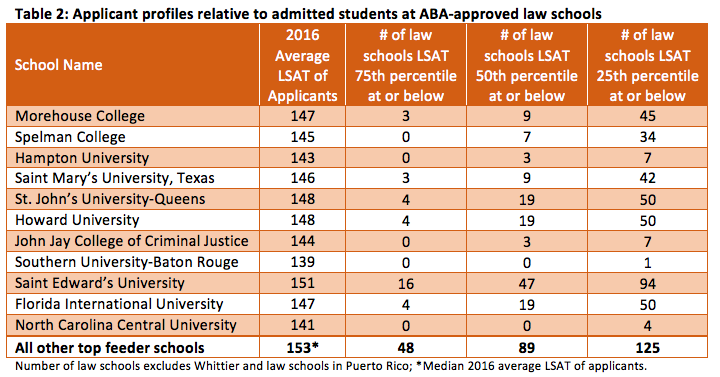

With lower admission credentials, applicants from these schools may have more limited law school options. Table 2 shows the average LSAT scores of the applicants from MSI feeders with high applicant concentration as well as the number of ABA law schools with 75th, 50th and 25th percentile LSAT scores at or below that level. Only a fraction of ABA law schools matriculated students in 2017 with LSAT scores at or below the average LSAT scores of these applicants.

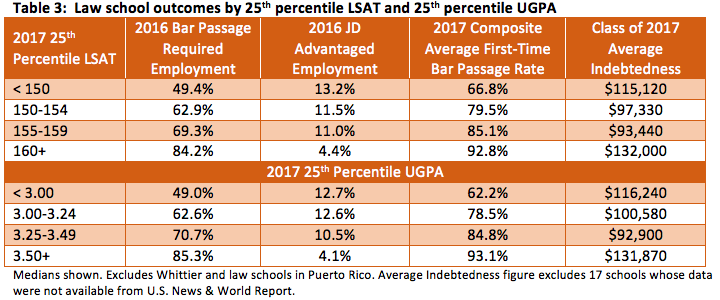

Furthermore, law school options for these applicants may be limited to those with suboptimal post-JD outcomes. Table 3 shows employment, bar passage and debt outcomes of law schools by their 25th percentile LSAT and by their 25th percentile UGPAs. Graduates of law schools with lower 25th percentile LSAT scores and UGPAs are less likely to be employed in bar passage required careers and to pass the bar on the first attempt; and in some cases, are more likely to have higher average debt than graduates of law schools with higher median LSAT scores and UGPAs. These metrics should not merely be attributed to incoming student credentials. Several schools, such as Pace University School of Law and St. Mary’s University School of Law, maintained first-time bar passage rates above 70 percent in 2017 while admitting students with LSAT scores below 150. These examples demonstrate that demography is not destiny, as law schools have a responsibility to educate and support the students they accept.

MSI feeder schools with high applicant concentration represent one of many opportunities for law schools to diversify their entering classes as well as the legal profession. Students most hungry for a law career should not be limited to institutions that represent a riskier investment of the time and money required to obtain a law degree. Supporting pre-law programming at MSIs and other schools with high applicant concentration but lower admission credentials is a critical and necessary step to ensuring access to legal education and equity in the law school admission process.

Implementing truly holistic law school admission practices is equally paramount to these goals. Undergraduate GPA and LSAT score are important considerations but should be evaluated within the context of other academic indicators and applicant characteristics, as others in the field have proposed. For example, Aaron Taylor, Executive Director of the Center for Legal Education Excellence, suggests adopting an Achievement Framework that privileges academic overachievers and socioeconomic overcomers. And professors Marjorie Schultz and Sheldon Zedeck developed a test of “Effectiveness Factors” to better evaluate students’ lawyering potential. Such paradigms offer alternatives that, if adopted, could mitigate racial and socioeconomic gaps that persist in legal education due to an overemphasis of test scores and GPAs in the admissions process.